Baltimore, Md. – It’s a painfully muggy day at Pimlico Race Course and 30,000 are gathered under the blazing sun for day two of Moonrise Festival.

Backstage, one of the revelers has somehow stumbled into the trailer of one Claude VonStroke and has begun to direct a soggy, but no less enthusiastic fanboy spiel toward the L.A.-based DJ/producer just minutes before he’s to take to the decks for a headlining set.

After a brief, but cordial exchange, the jacked-up fan finally, if confusingly, blurts: “You are my fucking dad!”

Surprisingly, VonStroke—otherwise known as Barclay Crenshaw—seems completely unfazed by the intrusion, or the inexplicable comment.

“I get this a lot,” he offers with a big grin. “I get this every day.”

Indeed, less than an hour before this strange encounter, the affable DJ was outside, personally grilling up ribs for a line of contest-winning superfans, while engaging in far more than the sterile meet-and-greet conversation.

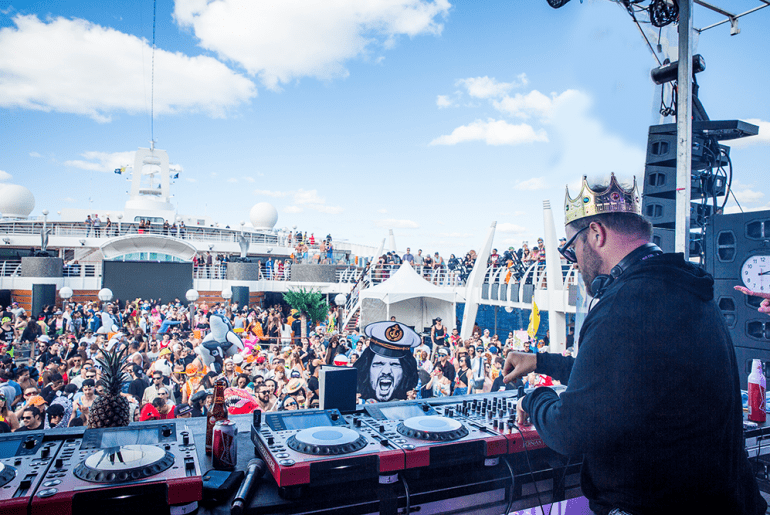

You see, he’s truly a man of the people. While most performers are bequeathed a godlike status by elevated DJ booths and larger-than-life pyrotechnics, Crenshaw is on a mission to prove that the only things separating from the clubbers are a pair of Pioneer CDJ-2000s and a table.

In a world of $10,000-a-table VIP sections and thigh-sized bottles of Belvedere vodka in nightclubs, it’s an unorthodox mentality for a DJ to have. However, given that the origins of his Dirtybird label stretch back to DIY gatherings in San Francisco’s Golden Gate Park over a decade ago, it’s no wonder Crenshaw rejects the idea of living his life beyond a velvet rope.

As the story goes, Dirtybird hatched in San Francisco from a group of like-minded friends—Worthy, brothers Justin and Christian Martin, and Crenshaw himself—who began to throw impromptu parties featuring groovy beats and piping-hot BBQs with a roaming soundsystem before its members started to churn out tunes themselves.

Those first few years laid the eggs for the collective’s massive influence on American underground dance music, with Claude VonStroke himself being responsible with for a pair of its particularly seminal releases: the croaky rumbles of the cheeky “Deep Throat” in 2005 and the synth-lead melancholy ode to his hometown “Who’s Afraid of Detroit?” in 2006.

In the years since its formation, the core family of Dirtybird has expanded to include other party-ready favorites like J.Phlip, Ardalan, and Kill Frenzy, all of whom have helped the imprint earn its reputation as a purveyor of a style they’ve dubbed booty-bass. Combining the funky swagger of hip-hop with the basslines of tech-house, it’s a genre that manages to split the difference between club-ready grooves and festival-primed drops and caused the group to steadily amass a devoted following thanks to its lack of pretension and good vibes.

This populist movement seems to have come to a head this year. After celebrating a decade of Dirtybird in 2015 with a series of anniversary parties across the country and the three-day Dirtybird Campout festival in Southern California, Crenshaw was voted America’s Best DJ 2016 by his rabid fans all over the country.

Ahead of his official crowning at Omnia San Diego, we caught up with the Big Bird himself to dive deep into just what’s gone into his and the Dirtybird’s stratospheric ascent to the top of the American dance scene and how it left big-room EDM, dubstep, and trap in the dust.

DJ Times: You celebrated a decade of Dirtybird last year, 10 years of “Who’s Afraid of Detroit” this year, and you just were voted America’s Best DJ 2016. What’s that like?

Barclay Crenshaw: [laughs] It’s kind of a shock to win this because I always thought of us [Dirtybird] as a really underground label and that we were galaxies away from these top guys that are just dominating the universe. It’s amazing that people would vote for me and vote for our sound.

DJ Times: It speaks to the proliferation of Dirtybird in recent times. Why do you think the label and the events have been such a hit, especially in the last two or three years?

Crenshaw: I will definitely say that there were two things that were significant: 1) I had a sub-label that was sucking a lot of time up—it was awesome, but I had to kill my baby and just say we’re concentrating on Dirtybird—and 2) I said, “We’re just going to try to crush at our home, and I’m not going to go to Europe 40 times for like the next two years.” That was a conscious decision, and I’m paying for it in Europe a little bit, but we actually said that we were going to really concentrate on making our parties great and making everyone feel like they belong there, making sure all the artists feel at-home when they come play for us. Even at The Birdhouse events that aren’t Dirtybird, our whole philosophy is to take care of the artists, make them happy, give them presents—

DJ Times: Make them want to come back.

Crenshaw: Yeah. Sometimes I’ll show up to a festival stage, and they’ll be like, “Yeah everybody drank all the booze. We have a quarter of a bottle of peach schnapps and some orange juice in the corner, and the sound guy went home.” We never want that to happen at any of our parties.

DJ Times: With Dirtybird, it feels as though the event portion is just as important as the music and the label itself. What impact do you think the Dirtybird BBQs—even going as far back as the original ones—had on the identity of Dirtybird?

Crenshaw: I think you if you go to one of our parties that we throw—not a promoter—you can really see what the group of friends is all about and how the company is run as a family. You can get the vibe that we’re just happy to be doing it, and that we want to have fun. It’s not really that serious. We want to be professional, but we’re not serious, mean people.

DJ Times: It splits the difference of the all-inclusive nature of an EDM festival and the tech-house scene, but it doesn’t have the pretentiousness of those underground clubs.

Crenshaw: I mean, we just want it to be fun. That’s all we’re striving for: fun for everyone, from the guy cooking the food to the DJs to everyone.

DJ Times: It feels like all of the 10 years of work culminated last year with Dirtybird Campout. Not many labels can throw a three-day festival.

Crenshaw: It changed everything for us, I think.

DJ Times: When did the first rumblings of that happen?

Crenshaw: That was just an act of will. I couldn’t get it to happen, so I said, “I don’t give a shit—we’re doing it anyway.” So I made a flyer, and I posted it on the internet with no venue, no production partner, no date, and nobody saying they’d play it. We had… “maybe these people will do it and maybe these people will do it,” but we didn’t like the choices, and my No.1 choice was Do Lab, but they were doing something else when I wanted to do it. Because I posted the flyer—to which everyone called me saying, “Are you fucking insane? Because you aren’t doing this party”—Do Lab said, “We just saw this flyer online. If you still need help…” I said, “Oh my god! Let’s meet up in Venice and have a meeting!” Three days later we signed a contract. It’s incredible. I’m so happy they came on board because they were the perfect partners—they’re just like us. It just worked out.

DJ Times: Dirtybird seems to have become very intertwined with festival culture in the past few years, whether it’s seeing kids wearing bracelets dedicated to it or pins, hats, etc. The Holy Ship! crowd in particular seems to have latched on; it feels like that was a big moment for the brand.